Long time fan Jack Snow had always, but always, dreamed of writing Oz stories, going so far as to offer to take over the series back in 1919, shortly after Frank L. Baum’s death. Not surprisingly, Oz publishers Reilly and Lee balked at the opportunity to place their major cash cow in the hands of an inexperienced and unpublished nineteen year old fan whose main qualification was extreme enthusiasm, turning to the proven children’s author Ruth Plumly Thompson instead. A disappointed Snow entered the radio business. In the next several years, he sharpened his verbal skills, writing for various radio stations (mostly NBC) and penning the occasional horror story for Weird Tales.

His interest in Oz, however, never faded, and when he heard that the death of John R. Neill had left Reilly and Lee once again scrambling for an Oz author, he eagerly campaigned for the position, this time marketing himself as both an Oz fan and an experienced writer (if not a novelist.) The pitch worked, or perhaps Reilly and Lee were desperate: in any case, Jack Snow was the next Historian of Oz. It was the beginning of a brief (only two books) and unpleasant business relationship.* But if the business relationship was disappointing, for readers, The Magical Mimics of Oz, is anything but.

*One of the most mysterious aspects of the entire Oz series is how it survived an ongoing tumultuous relationship between the authors and publishers. In going through the series, I could not find one author even marginally happy with Oz publishers Reilly and Lee; the more usual reaction was resentment, fury or bewilderment.

From the outset, Snow, no fan of Thompson’s whimsical (not to mention occasionally racist) approach to Oz, and her introduction of traditional (and European) fairy tale elements and quests, made a conscious choice to return to the original tone and world created by Frank L. Baum, ignoring the developments and characters created by Thompson and Neill. (Thompson thoroughly approved; as a living author, she did not want her characters used by another author in the series. Although this same issue was not, of course, true for the characters created by Neill, my guess is that Snow, reading those books with the same bewilderment many fans did, would have been at a loss to figure out how to use any of Neill’s creations.)

Snow also attempted, with some success, to imitate Baum’s writing style, going so far as to restore Baum’s later habit of giving nearly every character, no matter how minor, some cameo appearance, even bringing back such obscure characters as Lady Aurex from Glinda of Oz and Cayke and the Frogman from The Lost Princess of Oz

Snow could not, however, quite reproduce Baum’s easy humor. This may have stemmed from personality differences, or perhaps the dark years of World War II played a role in dimming Snow’s taste for comedy. Snow had received a medical discharge from the U.S. Army Air Corps in 1943, and thus spent most of the war in the United States safe from combat, but this did not allow him or others the luxury of completely escaping the war, and the resulting tension fills the book.

But these are carpings: Magical Mimics is not merely far closer to the original Baum series than any of the other Famous Forty books, but a good book on its own, easily among the best of the Oz sequels.

The book opens with a pensive Ozma deciding to hand over the rulership of Oz to Dorothy while the young Ruler flitters off to what she calls an important conference with fairies and the rest of us call a vacation. The rightfully appalled Dorothy points out her age and inexperience, but Ozma, displaying her characteristic inability to listen to good advice, flutters off anyway.

As Dorothy feared, that decision is almost catastrophic. Some of Oz’s fiercest, most resentful enemies, the Mimics, have been watching closely, quite aware that Ozma’s security systems are, as we’ve been noting for some time, quite lacking, and without Ozma, could be best described as “non-existent.” They seize the chance to capture Dorothy and the Wizard, speeding them to a prison outside Oz. The two rulers of the Mimics then use their magical powers to, well, mimic the appearances of Dorothy and the Wizard (Oz would not be Oz without puns). The substitution is made so smoothly and so well that even Dorothy’s closest friends do not initially suspect a thing.

This sets up two intertwined plots: Dorothy and the Wizard’s escape from prison, and the slow takeover of the Emerald City by the Mimics, a takeover that its residents seem largely powerless to prevent. Indeed, at first they are unaware of any takeover attempts, noticing only that the false Dorothy and the Wizard are acting strangely and being rather secretive. It takes the sharp nose of —Totohere taking a major role for the first time in several books—to sense that more is going on.

Meanwhile, Dorothy and the Wizard, with a little help, find themselves in Pineville, a city of people made of wood who, oddly enough, seem to like log fires. Their escape inexplicably causes the already not very good illustrations to drop even further in quality. They also find Ozana, who might, perhaps, look like Ozma, not that this can be determined from the illustrations, and Ozma’s fairy cousin, who confesses that she was responsible for keeping the Mimics imprisoned. Quite unlike her cousin, Ozana is refreshingly willing to take responsibility for her failures as a jailor.

As I noted, shadows of World War II infuse the book, from the allusions to Fifth Columnists and uncertainty of the true identities and loyalties of supposed friends (always a concern in a world afraid of spies), to the failure of trusted deterrents and supposed defenses, to the proud ability to carry on with daily activities and delights, no matter what the threat. Cap’n Bill, for instance, echoing behavior Americans took pride in during the war, chooses to continue his wood carving while waiting for Uncle Henry to return with strategic information. And, following the ideals publicized by wartime propaganda, the citizens of the Emerald City take care to respond with dignity and calm good sense. (Even Ozma.) It allowed Snow to transmute the daily horrors of World War II, even those experienced from miles away, into a fairy tale, one offering hope that balance, joy and safety might soon return.

If, as a result, these shadows create a book considerably darker than its immediate predecessors, “dark” is a comparative word in Oz terms, and Snow’s tone is not unprecedented: I found it less dark and troubling than a couple of the Baum books, and certainly less troubling than the casual racism in some of the Thompson books. But a chief difference between Magical Mimics and its immediate predecessors is that Snow takes Oz seriously. The casual racism in some Thompson books is horrifying because Thompson handles it so lightheartedly. Snow believes in Oz, and he does not excuse his villains.

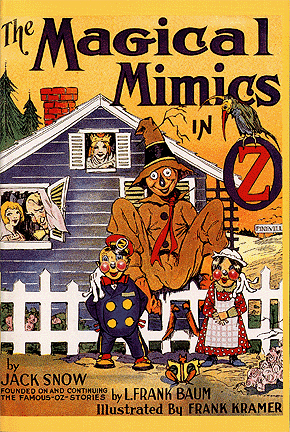

If the text is compelling, the illustrations are…decidedly not. At best, Frank Kramer’s work is a poor knock-off of John R Neill’s delightfully imaginative, elaborate work or the worst of the Disney cartoons; at worst (which is most of the illustrations), the pictures are shoddy and unattractive, especially those that look like knock-offs of the worst of the Disney cartoons. Completely gone are the delightful whimsy and the tiny details Neill tucked into his sketches to delight the observant. Since Kramer later had a successful career illustrating children’s sports novels, I can only assume that he simply had no gift for fantasy art (and seemingly no imagination whatsoever). I strongly recommend reading text-only versions of this and its sequel, The Shaggy Man of Oz, unless another illustrator decides to take on these books. You won’t be missing anything.

Wartime paper shortages delayed the publication of Magical Mimics. By the time the book was finally published in 1946, the Oz series had suffered a three year delay, and the somber wartime tone had begun to pass. These factors, combined with poor timing (Reilly and Lee, displaying their usual flair for thoughtlessness and poor marketing, apparently failed to get the books delivered in time for Christmas sales), the low quality of its predecessors, and art that simply doesn’t “look like” Oz (and just isn’t any good), and an unknown book author all probably led to the book’s poor comparative sales.

And some readers, and certainly some libraries, may have had another problem.

I eagerly searched for this book when I was a kid, only to be coldly told by our local library that Jack Snow was “inappropriate” for young readers. (Naturally, this made me want to read it more.) This was not a hatred for Oz or its sequels: this same library had copies of most of Thompson’s books (if not the overtly racist ones) and of Hidden Valley of Oz and Merry-Go-Round in Oz.

No, I fear for “inappropriate,” we must read “gay.” I have no idea how widely this was known, if at all, when Mimics was originally published, and I can’t find any hints of sexuality of any kind in either of Snow’s Oz books. Like Baum, Snow left romantic plots, straight or otherwise, out of his books, and even his married characters give a decidedly asexual feel. In Snow’s Oz, as in Baum’s, sex just doesn’t happen. But by the 1980s, at least, Snow’s sexual orientation was apparently well enough known to keep his books out of some children’s libraries, and deprive them of some wonderful moments in Oz.

Mari Ness lives in central Florida. It’s entirely possible that her two cats are not, in fact, cats at all, but rather two aliens mimicking cats. She is not sure how anyone could tell the difference.